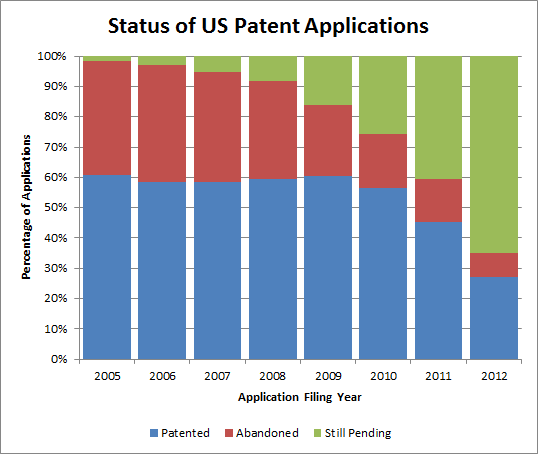

It shows that for all cases that were filed before 2010, the number of patented cases as a percentage of the total is about 60%, and that the principal change is pending cases going abandoned. This suggests that if you've got an application that was filed before 2010 and it's still pending, your chances of getting it allowed are slim.